A version

of the following appeared as a feature article in the

April, 1999, edition of American Art Review: A version

of the following appeared as a feature article in the

April, 1999, edition of American Art Review:

At the

end of 1971, just after Mabel Alvarez turned eighty, she

decided to give up the Beverly Hills apartment/studio where

she'd lived and worked for thirty years and move into the

elegant Fifield Manor retirement home in Hollywood, originally

the Chateau Elysée,

built as an apartment hotel in the 1920s by William Randolph

Hearst. A friend of mine lived there, and that's where I

met this amazing woman who was to become my friend.

Suddenly Miss Alvarez found herself among an

assortment of "old

people," that

included a widowed member of the Danish royal family, a courtier-dressed

octogenarian alcoholic, whose prominent family had parked

her at Fifield to minimize embarrassment, who lurked in her

doorway enticing with tumblersful of straight bourbon any

male who happened by, and a tall, sepulchral lady who cluttered

the elegant French drawing room with the scraps of paper

that comprised her vast collection of postmarks. Watching

these "inmates," as Mabel referred to them,

sitting hunched over their meals in the dining hall she likened

them to a bunch of Trappist monks. She wrote in her diary, "How

boring they all are - talking only about who is in the hospital

with the latest broken hip, etc., etc. Pathetic. They have

no inkling of the strange wonders in the world I encounter

every day."

This tall, slender, always beautifully

turned out Miss Alvarez, usually dressed in some shade of

green, was well-read in both English and Spanish literature,

and for some reason, despite the several-decades difference

in our ages, each of us found the other interesting. We became

close friends and remained so for the last dozen years of

her life.

Eventually, a broken hip took its toll

on Mabel's body, though her mind never grew old. She was

forced to move to a nursing home. She came to rely on me

to keep her in touch with the outside world. Once I took

her, in her wheelchair, to the opening party of a Los Angeles

County Museum of Art exhibition, which included one of her

pictures. An elderly European gentleman rushed up to Mabel

and kissed her hand. He said he'd admired her work for many

years and had always wanted to meet her. He'd been a friend

of Modigliani and was one of his pallbearers in Paris in

1920.

As it is with anyone, to understand Mabel

Alvarez it is necessary to know a little about the environment

in which she grew up. The youngest of the five children of

Dr. Luis Fernandez Alvarez and the former Clementine Setza,

Mabel was born in an old converted Anglican church, complete

with bell tower, at Waialua, near the north shore of Oahu

Island, Kingdom of Hawaii, on 28th November 1891, the first

year of the short reign of Queen Liliuokalani.

Mabel's father was a native of the Asturias

region of Spain. Her paternal grandfather was the business

manager for El Infante Don Francisco de Paula, third son

of King Carlos IV of Spain and great-great-great grandfather

of Spain's present King Juan Carlos. Mabel's mother, a talented

and accomplished pianist with a beautiful singing voice,

granddaughter of a German sea captain, was a member of a

prominent St. Paul, Minnesota, family of musicians that included

Uncle Charles Schütze, a composer and, according to

newspaper clippings and concert programs, "the greatest

concert pianist in the Northwest." Cousin

Mildred Potter, an operatic contralto who Mabel said "sang

with Jenny Lind" (the famous "Swedish Nightengale" of

the 19th century), was, according to family records, the

only American of her time to sing at the Metropolitan Opera

without first having sung professionally in Europe. Another

cousin, a Mr. Pottgeiser, was a concert pianist of some renown.

It was, therefore, through her mother that Mabel and her

brother Milton (who died in the Philippines of a tropical

disease while still a young man - the only one of the five

siblings not to live more than 89 years) came by their artistic

talent. The rest of the family were, to one degree or another,

scientists, taking after their remarkable father. Mabel's father was a native of the Asturias

region of Spain. Her paternal grandfather was the business

manager for El Infante Don Francisco de Paula, third son

of King Carlos IV of Spain and great-great-great grandfather

of Spain's present King Juan Carlos. Mabel's mother, a talented

and accomplished pianist with a beautiful singing voice,

granddaughter of a German sea captain, was a member of a

prominent St. Paul, Minnesota, family of musicians that included

Uncle Charles Schütze, a composer and, according to

newspaper clippings and concert programs, "the greatest

concert pianist in the Northwest." Cousin

Mildred Potter, an operatic contralto who Mabel said "sang

with Jenny Lind" (the famous "Swedish Nightengale" of

the 19th century), was, according to family records, the

only American of her time to sing at the Metropolitan Opera

without first having sung professionally in Europe. Another

cousin, a Mr. Pottgeiser, was a concert pianist of some renown.

It was, therefore, through her mother that Mabel and her

brother Milton (who died in the Philippines of a tropical

disease while still a young man - the only one of the five

siblings not to live more than 89 years) came by their artistic

talent. The rest of the family were, to one degree or another,

scientists, taking after their remarkable father.

And what scientists they were! Mabel's

elder brother, Dr. Walter C. Alvarez, was the noted Mayo

Clinic physician-research scientist, syndicated columnist,

lecturer, and author of many common-sense books on medical

subjects for the layman. His newspaper column ran every week

for more than thirty years in most of the country’s

major newspapers. His autobiography, Incurable

Physician (Prentice-Hall, 1963), was a best-seller.

Dr. Luis Alvarez, Walter's son, long

associated with the University of California, Berkeley,

was a member of the Manhattan Project and later a senior

member of the team of atomic scientists at the Lawrence

Livermore Laboratory. Among his many other achievements

were the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1948 for his

invention of the first all-weather landing system for aircraft

(which President Truman said had made the Berlin Airlift

possible), work in the field of stabliized optics that

resulted in binoculars and cameras that maintain stable

images in such unstable atmospheres as helicopters, with

his son Walter, the renowned archaeologist (author of T-Rex

and the Crater of Doom, (1997, Princeton University

Press)) the generally-accepted theory that the dinosaurs

disappeared as a result of the collision of an asteroid

with the earth, and the 1968 Nobel Prize for Physics.

Upon graduation from the Cooper Medical

College in San Francisco (now Stanford University School

of Medicine), Mabel’s

father was offered the position of assistant to the chair

of nervous diseases at Cooper, but at that point he was very

tired and he felt that he needed first to take a break to

restore his health. To benefit from the sea air he booked

as the physician on a steamship bound for Hawaii. When he

arrived in Honolulu in 1888 he learned that King Kalakaua's

government was looking for a doctor to care for the plantation

workers who were just then beginning to migrate there from

the newly-opened-up Japan (the very first Japanese to settle

anywhere outside Japan) and from China. Mabel always suggested

that King Kalakaua had a direct hand in the hiring of her

father, and a clue as to why is offered by David Forbes in

his book Encounters

With Paradise, Views of Hawaii and Its People, 1778 - 1941 (published

by the Honolulu Academy of Art, 1992.). There having been

quite a bit of tension between Hawaii and Japan arising

from reports that the Japanese sugar cane plantation workers

were being ill-treated, King Kalakaua had gone so far as

to commission the artist Joseph Strong (Robert Louis Stevenson's

son-in-law) to paint a large picture depicting the contented

Japanese workers on Claus Spreckels' plantation to present

to Japan's Emperor Meiji. It is reasonable to believe that

hiring a doctor to care for their health was part of this

pacification campaign. (The Joseph Strong painting is now

in a corporate collection in Tokyo and is reproduced in

Mr. Forbes' book and in Nancy Dustin Wall Mouré's California

Art - 450 Years of Painting & Other Media (Dustin

Publications, 1998).)

Mabel's father learned the Hawaiian

language fluently, and he also spoke Spanish, English,

and French. But he had little success gaining the confidence

of his Asian patients until one Chinese family found its

ox, so necessary to their survival, sick and near death.

As a last resort they decided to ask this strange white

doctor to help. The ox was soon cured, and at least one

barrier fell. These and other difficulties of the young

Dr. Alvarez, in his first years in Hawaii, are reflected

in his amusing writings, which are in the Alvarez archive

at the Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, and in the Mabel

Alvarez papers in the Archive of American Art, Smithsonian

Institution, in Washington. Mabel's father learned the Hawaiian

language fluently, and he also spoke Spanish, English,

and French. But he had little success gaining the confidence

of his Asian patients until one Chinese family found its

ox, so necessary to their survival, sick and near death.

As a last resort they decided to ask this strange white

doctor to help. The ox was soon cured, and at least one

barrier fell. These and other difficulties of the young

Dr. Alvarez, in his first years in Hawaii, are reflected

in his amusing writings, which are in the Alvarez archive

at the Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, and in the Mabel

Alvarez papers in the Archive of American Art, Smithsonian

Institution, in Washington.

It wasn't long before the Alvarez family

moved into Honolulu, into what the 1899 book Hawaii Nei called "a

fine place on Emma Street." Dr.

and Mrs. Alvarez became friendly with Queen Liliuokalani

and her yankee husband, John Owen Dominis, and Dr. Alvarez

served as physician to the Queen.

Mabel told an amusing story that when

the family was still living at Waialua Mr. Dominis would

ride his horse out to spend weekends with them, telling Queen

Liliuokalani that he was going there for a weekend of hunting.

No fool she. Mr. Dominis had a fondness for strong drink,

and she knew he was just getting away from her for a weekend “toot.” So

just before sundown on the Sunday afternoon the queen’s

coach could be seen approaching in the distance. She knew

that by that time he would be greatly the worse for drink

and unable to ride his horse back reliably. So he was piled

into the coach, his horse tied on behind, and they returned

to Honolulu. When he was drunk the queen wouldn’t allow

him into Iolani Palace, so he was obliged to remain in an

outbuilding on the palace grounds, built for just that purpose,

until he was again presentable.

After Liliuokalani was forced to abdicate

in 1893, Dr. Alvarez went to Baltimore to learn all that

was known about leprosy at John's Hopkins University and

returned to Hawaii to continue the leprosy research begun

by the legendary Father Damien. His title was Superintendent

of the Experimental Hospital for the Treatment of Leprosy.

Aided by the recent invention of the microscope, he developed

a method of diagnosing the disease in its earliest stages,

before any symptoms were visible. He also discovered that

the leprosy bacillus is spread by mosquitoes. He represented

the Republic of Hawaii at the World Lepra Conference in Berlin

in 1897, conferred with the Norwegian Dr. Hansen, who had

recently discovered the leprosy bacillus (it's still sometimes

called "Hansen's

disease"), and lectured on the subject at the Pasteur

Institute in Paris and other places.

The King of Spain appointed Dr. Alvarez

to the honorary post of Spanish Consul to Hawaii, and he

later served for many years in the same position in Los Angeles.

For this service he was awarded the Order of the Crown by

King Alfonso XIII.

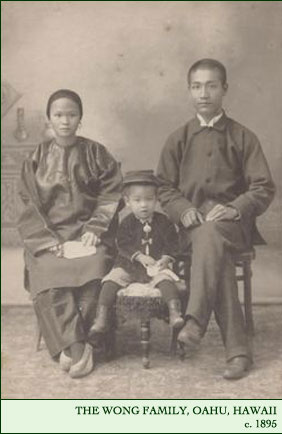

So you can see that Mabel grew up in a

home forever tingling with intellectual energy and associations

with interesting people. Their society soon included not

only Queen Liliuokalani, but also the Judds, the Castles,

the Cookes, the Halsteds, and - last but not least - Dr.

Alvarez' friend (and, as Mabel always said, a rare intellectual

equal), the aristocratic young Mr. Wong, said to be the first

Chinese graduate of Harvard. A c.1895 photo portrait of Mr.

and Mrs. Wong and their young son survives.

In addition to the family's spacious home

on Emma Street, Honolulu's equivalent of Millionaire Row,

Dr. Alvarez owned a great deal of real estate in downtown

Honolulu. The land boom of the 1890s and early 1900s made

him a wealthy man. A few years after Hawaii became an American

protectorate, Dr. Alvarez felt that his work there was done. In addition to the family's spacious home

on Emma Street, Honolulu's equivalent of Millionaire Row,

Dr. Alvarez owned a great deal of real estate in downtown

Honolulu. The land boom of the 1890s and early 1900s made

him a wealthy man. A few years after Hawaii became an American

protectorate, Dr. Alvarez felt that his work there was done.

Mabel's sister Florence told an interesting

story to explain why they left Hawaii. Their mother, Florence

said, was very much disturbed when a young man told her he

had married a beautiful Hawaiian girl and now they had a

small daughter. He realized he was trapped forever in the

Islands, because his wife and daughter would be considered

black in the United States. Mrs. Alvarez thought of her own

children approaching marriage age and felt it was time to

go.

Mabel’s version was quite different.

She said that a young haole (white) lady, for some reason,

came to Dr. Alvarez to be tested for leprosy and, though

she showed no symptoms, she tested positive. Under Hawaiian

law that meant mandatary removal to the leper colony on Molokai,

where she’d

have to spend the rest of her life. She begged Mabel’s

father to let her go home, promising to turn herself in at

the first visible symptom of the disease. He felt sorry for

her situation and covered for her. But before long her lesbian

lover turned her in, and it caused a stir that involved Dr.

Alvarez. And that, Mabel said, was when they decided to leave

the islands.

In 1908, the family settled into a large

Victorian mansion on West 25th Street in Los Angeles, in

what was then a fashionable district near the campus of the

University of Southern California (USC). Dr. Alvarez devoted

the remainder of his life (he worked almost until the day

he died in 1937), to the practice of medicine, with little

regard for fees, among the poor predominantly Mexican population

of Los Angeles.

From her earliest childhood, Mabel was

clever at drawing. There survives a delightful group of her

childhood drawings, including a set featuring a little girl

in high-button shoes in various poses with Easter lilies,

Easter card designs that Mabel made for her and her sister

Florence. Some of these drawings were shown in the 1999 Mabel

Alvarez retrospective exhibition at Loyola Marymount University,

Los Angeles, and at the Orange County Museum of Art in Newport

Beach.

Mabel's artistic talents were discovered

and encouraged by her high school art teacher, James E. McBurney.

Through his efforts she was invited to produce a large mural

for the Pan-California Exposition in San Diego in 1915-16.

It won her the Silver Medal, and from that time forward Mabel

never had the slightest doubt that her life would be devoted

to art.

In 1915, she enrolled in Los Angeles'

leading art school, the School for Illustration and Painting,

founded by John Hubbard Rich and William V. Cahill. She showed

a talent beyond both her years and her training. Her haunting

charcoal portrait of a woman in profile (seen in the Will

South essay reproduced here) was used by the school as the

cover of its catalogue well into the 1920s. The original

drawing survives in her estate, and copies of the catalogue

are in the Smithsonian.

Her father recognized that she was both

talented and serious about a career in art, so he arranged

for her financial security that made it possible for her

always to try every new idea that appealed to her and to

stay with each idea only for as long as she felt inspired

by it, never making any compromises to the marketplace For

example, her most famous painting, her 1923 "Self-portrait," which

forms the cover of the popular art book Independent Spirits,

Women Painters of the West by Dr. Patricia Trenton

(University of California Press), brought a generous purchase

offer from Mrs. Arabella Huntington (the Huntington Library

and Art Museum in San Marino, California) soon after she'd

completed it. Mabel had no interest in selling it to even

so important a collector, because she knew that Mrs. Huntington

meant to hide the picture away in her home in New York.

During the Industrial Revolution, primarily

the few decades after about 1870, science influenced more

change in people's lives than perhaps during any previous

millennium since the beginning of mankind. That seems to

have caused many people, especially those such as the intellectual

and scientifically-inclined Alvarezes, to redefine the very

nature of religion. In many cases they turned away from the

traditional religions, at least from beliefs that seemed

to be contradicted by the new developments in science. Mabel's

parents had both been raised Catholic and had married in

the Catholic church in St. Paul. But, feeling that too much

of religious practice was exclusionary and in opposition

to their idea of the essence of religion, the Golden Rule,

they soon left the Church for the freedom to investigate,

question, and to weigh the teachings of all the world's religions.

The family attended the Congregational Church in Hawaii and

on the Mainland and maintained a sensitivity to the ideals

of religion. But there is no evidence that any of them ever

subscribed seriously to any established religion.

None of the family, it seems, searched

longer or more diligently for spiritual grounding than sensitive,

romantic and intellectual Mabel. She gives evidence of this

by returning time and again, all her life, to religious and

philosophical themes in her paintings. None of the family, it seems, searched

longer or more diligently for spiritual grounding than sensitive,

romantic and intellectual Mabel. She gives evidence of this

by returning time and again, all her life, to religious and

philosophical themes in her paintings.

Around 1918, Mabel met Will Levington

Comfort (she had, in fact, read his book, Child and Country,

as early as 1914), and she discovered the principles of Eastern

mysticism and what became known as Theosophy. She began attending

Comfort's lectures and meditation sessions at his establishment

in the Hollywood hills, and she became a regular visitor

to the philosophical "experiences" at

his home on Avenue 54 in Highland Park. Her involvement in

these and other modernist groups, a fertile ground for artistic

experimentation, deeply moved and transformed her in a way

that affected her art for the rest of her sixty-year career

- a career that continued for some thirty years beyond almost

all of her contemporaries.

During the 1920s and early 1930s, Mabel

executed a series of symbolic paintings which set the tone

of all the pictures she painted thereafter. They provide

tantalizing glimpses into her private dream world, where

all her wishes, hopes, longings and desires and her rich

imagination yearned for expression. Even the titles for her

pictures reflect that dream world: "Reverie" for

a large, pensive portrait of her sister Florence, "Silent

Places," "The

Brigham Nose," "With a Lion and A Unicorn" (the

unicorn in this context symbolizes the incarnation of Christ

and the principle of moral purity in action), "Variations

on an Icon," "Dream of Youth," "Myself

with Dreams of Youth," a magnificent self-portrait in

a soft but intense green dress surrounded by her dreams (romance,

music, religion, etc.) in vignettes.

Michael Kelley, in his 1990 essay "Dreams,

Visions and Imagination," stated, "The

spiritual ideals that Alvarez sought seemed to exist in a

parallel universe which was removed from the hard realities

of normal, everyday existence. Consequently, her symbolic

paintings are always staged in a distant idyllic world where

less than ideal realities cannot intrude and dreams have

become reality."

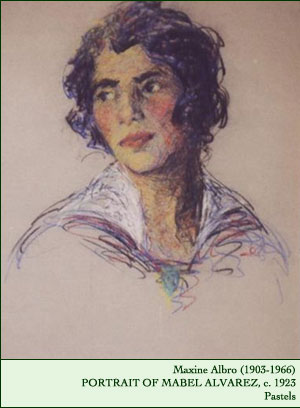

Even her portraits show this sensitivity.

It has been noted by critics that the 1923 self-portrait

shows evidence of some sadness in her heart at the time she

was painting it. What they hadn't known is that Mabel's mother

died while that picture was being created. She didn't mention

her mother's death in her diaries, but she painted it in

her portrait.

Another example is her stunning portrait "Abraham,

Hawaiian Boy" that

betrays a haunting vulnerability in an otherwise strapping

fifteen-year-old. It took me years waiting for a time when

she could remember what was so special about Abraham. Not

long before her death she remembered: Abraham was deaf-mute.

Mabel had painted it in his eyes.

The primary color that Mabel used to express

her personal symbols was green, many soft hues of green,

which represents joy, love, hope, youth, and mirth. These

were played out on a stage of canvasses in the forms of universal

ideals and archetypes: the child, the innocent maiden, the

alluring and seductive temptress, the faithful wife, the

spiritual seeker, the earthbound spirit in limbo, and the

liberated spirit that has transcended earth's constraints.

An entry in her diary in 1918, just as her work was beginning,

summed up her entire career, "I want to take all this

beauty and pour it out on canvas with such radiance that

all who are lost in the darkness may feel the wonder and

lift to it." Look at her work and you will see that

she meant it. All of her life her paintings expressed her

strong sense of passion and love of life, and they made real

her dreams and in so doing echoed the dreams of mankind.

One of the reasons so few of Mabel Alvarez' paintings come

to the market is that their collectors tend to connect so

personally with them.

One of several early champions of Mabel's

work was Arthur Millier, the longtime and powerful art critic

for the Los Angeles Times through the 1920s and '30s. "She

isn't a woman painter, she's an artist," he wrote of

Mabel, and he exposed her work and applauded her in the pages

of his newspaper many times.

During those years Mabel began a long

list of important exhibitions that included the Art Institute

of Chicago (1923), the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

in Philadelphia (1924 & 1937), the San Francisco Palace

of the Legion of Honor (1931), the Museum of Modern Art,

New York (1933), Budworth Gallery, New York (1934 & 1937),

Rockefeller Center (1935), the Golden Gate International

Exposition in San Francisco (1939), Honolulu Academy of Art

(1940 & 1992),

many exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

from 1920 to the present. In 1927, Mabel was on the committee

that accepted Aline Barnsdall's gift of her Frank Lloyd Wright

home, Hollyhock House, to the California Art Club.

Mabel always loved children. She took

a special delight in painting pictures that appealed to children.

But these pictures are not just cartoons or caricatures;

they are serious, intellectual compositions. Her nieces and

nephews and many of the other children she knew received

pictures of clowns (the one that I call Ferdinand, painted

for Luis' children in Berkeley, has personality to die for!),

toys doing funny tricks, children and animals with anatomical

features depicted incorrectly (such as a head turned backward,

a dog's hind legs facing the wrong way, the upper half of

a child's body facing one direction and the lower half turned

the opposite way). In 1929, Mrs. Samuel Goldwyn asked Mabel

to paint some pictures, one of which was a funny Santa Claus,

to decorate her small son's room (he is now the movie mogul,

Samuel Goldwyn, Jr.). These caught the attention of the Irving

Berlins when they visited, and Mabel was asked to paint a

portrait of their little girl. Mabel always loved children. She took

a special delight in painting pictures that appealed to children.

But these pictures are not just cartoons or caricatures;

they are serious, intellectual compositions. Her nieces and

nephews and many of the other children she knew received

pictures of clowns (the one that I call Ferdinand, painted

for Luis' children in Berkeley, has personality to die for!),

toys doing funny tricks, children and animals with anatomical

features depicted incorrectly (such as a head turned backward,

a dog's hind legs facing the wrong way, the upper half of

a child's body facing one direction and the lower half turned

the opposite way). In 1929, Mrs. Samuel Goldwyn asked Mabel

to paint some pictures, one of which was a funny Santa Claus,

to decorate her small son's room (he is now the movie mogul,

Samuel Goldwyn, Jr.). These caught the attention of the Irving

Berlins when they visited, and Mabel was asked to paint a

portrait of their little girl.

In 1929, The University of Southern California

commissioned her to paint the official portrait of the retiring

dean of its law school. Mabel told me that the poor, dying

man was so wracked with cancer that it took all her skills

to portray him in a manner that could please him and the

school. She succeeded.

In 1923 and 1924, Mabel and Kathryn Bashford,

her next-door neighbor and lifelong friend, traveled in the

eastern part of the country (New York, Boston, Philadelphia)

and in Europe, the first of several such trips over the years,

making personal contact with the world's great art that had

therefore been available to them only in mostly black and

white photos. After a stay in Paris, where Mabel soaked up

as much as possible of the work of, particularly, Cézanne

and Matisse, whose techniques she had studied for several

years, they moved on to Florence and then to Rome. There

they met a young scholarship student at the American Academy

of Music who was to become a friend. He was Howard Hansen,

later the famous American composer and director of the Eastman

Rochester Symphony Orchestra.

Mabel's stay in Paris was recalled in

1998, when the U. S. State Department mounted an exhibition

at Weber House in Paris of the paintings of eighteen of the

American women artists who were there in the half-century

between 1880 and 1930. Mary Cassatt, Henriette Wyeth, Mabel's

friend Henrietta Shore, and Mabel Alvarez were among those

represented.

In the early 1920s, Mabel met the artist

Stanton Macdonald-Wright. He recognized her talent immediately,

and she studied and consulted with him, drew encouragement

from him from that time to the end of his life.

In August of 1931, Morgan Russell, Macdonald-Wright's

collaborator in founding the Synchromy art movement in Paris

about 1912, arrived in Los Angeles from France for a protracted

visit. Russell had been a student of Cézanne

and Matisse, a protégée of Gertrude Vanderbilt

Whitney (New York's Whitney Museum of American Art), one

of the artists in the sphere around Gertrude and Leo Stein

in Paris, and later married to Monet's niece. For the remaining

twenty years of Russell's life Mabel was his student, his

confident, and his financial mentor. His letters to Mabel

are a part of the extensive Morgan Russell archive in the

Montclair (New Jersey) Museum. The Matisse-Russell artistic

legacy was a natural fit with Mabel's special characteristics,

and her work reflected it for the rest of her life, especially

in the joyous, colorful canvasses that she produced in her

last twenty years.

Mabel was one of those rare beings who

are comfortable with all kinds of people, low-born and high-,

rich and poor, black, white, brown and yellow, gay and straight

- - as long as the person was interesting. I think she was

a great deal less concerned whether the person was good or

bad - relative terms, withal - than whether he or she was

interesting. She was completely comfortable with Morgan Russell's

transvestism. She told me about going with him to Bullocks

Wilshire, the elegant Los Angeles department store. He wanted

a new corset for himself, and it would have been at least

awkward for a man to purchase such a garment in those days.

Mabel said they'd wait for the saleslady to turn away for

something, then Morgan would quickly hold the corset up to

himself to judge whether it was the correct size. After he'd

made his selection Mabel would buy the garment for him.

Mabel was, as anyone who has seen one

of her portraits knows, a strikingly beautiful woman, both

when she was young and after she became old. Men hoping for

romance, or at least a concupiscent relationship, flocked

around her. But she fended them off with the determination

of a lady of her class and of her time. So I was amused and

somewhat surprised to read in her diaries of her erotic jousting

with the sculptor Karoly Fulop (“He has X-ray eyes

(seemingly all men do),” she wrote) and her little

nocturnal window curtain games with the much older Englishman

Mr. Culley across the street from their home in Hancock Park.

And there was the suitor to whom she wrote poems that she

didn't send and whom she only referred to as "G" and

a Mr. Dickson who expressed "desperate" love for

her. Her relationship with Bob Kennicott seems more romantic

than erotic, which probably explains why she pinned such

hopes on him.

Early in 1932, Mabel met, through her

brother Walter, the prominent Beverly Hills physician, Dr.

Robert Kennicott. Among his patients and/or intimates (much

to the consternation of Mabel's "socially dedicated" sister

Florence, who glided through the Great Depression in the

family's magnificent Packard, safely sealed off from the

country's problems and Mabel's "arty" friends)

were Agnes DeMille (not only had Bob removed her appendix,

but they had once been engaged), Jean Harlow (when her husband

hanged himself from a tree Bob was called to identify the

body), the Edward G. Robinsons, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary

Pickford, and Ralph Bellamy and one or two of Bellamy’s

procession of wives. Bob's favorite pastime was sketching

and painting and attending every sort of art function. He

and Mabel were a natural match. Outings to the country to

sketch, sharing models, entering little exhibitions together,

they were almost inseparable throughout the decade, during

which Mabel's fantasies of marriage and the "happy ending" seemed

ever on the verge of reality. Her diaries (now in the Archive

of American Art, Smithsonian) mention numerous occasions

when they were assumed to be husband and wife at social events,

or someone would ask her if she was Mrs. Kennicott, and she

would be over the top for days. Early in 1932, Mabel met, through her

brother Walter, the prominent Beverly Hills physician, Dr.

Robert Kennicott. Among his patients and/or intimates (much

to the consternation of Mabel's "socially dedicated" sister

Florence, who glided through the Great Depression in the

family's magnificent Packard, safely sealed off from the

country's problems and Mabel's "arty" friends)

were Agnes DeMille (not only had Bob removed her appendix,

but they had once been engaged), Jean Harlow (when her husband

hanged himself from a tree Bob was called to identify the

body), the Edward G. Robinsons, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary

Pickford, and Ralph Bellamy and one or two of Bellamy’s

procession of wives. Bob's favorite pastime was sketching

and painting and attending every sort of art function. He

and Mabel were a natural match. Outings to the country to

sketch, sharing models, entering little exhibitions together,

they were almost inseparable throughout the decade, during

which Mabel's fantasies of marriage and the "happy ending" seemed

ever on the verge of reality. Her diaries (now in the Archive

of American Art, Smithsonian) mention numerous occasions

when they were assumed to be husband and wife at social events,

or someone would ask her if she was Mrs. Kennicott, and she

would be over the top for days.

But, alas, marriage never came, to Dr.

Kennicott or to anyone else. By 1939, the little signs that

had accumulated in her mind over the years suddenly, and

shockingly, added up to a suspicion that she had hitched

her dreams to a gay man who would never give her marriage.

Many years later I became acquainted with Adrienne Tytla,

the widow of Will Tytla, the Disney animator who created

Dumbo, and a friend to and model for Mabel during the 1930s.

Adrienne said to me, "I knew Bob was gay the first time

I met him; I can't imagine Mabel was so naive that she took

that long to figure it out."

Occasions such as that called for people

of her class to go away and clear their heads for a few months.

(The lower classes, for whom such long hiatuses weren't an

option, simply fought it out and the survivor went on with

his or her life.) After all, Mabel had already caused poor

old Mr. Culley across the street to flee to Northern California

for some months. His passion had mounted until he was eventually

emboldened to address her by her Christian name and to touch

her arm - whereupon she rebuked him - whereupon the poor

man deposited at her back door under cover of darkness the

Renoir folio she'd loaned him. And then he left town to clear

his head.

As luck would have it, at that very time

a friend of Mabel's, who lived in an apartment on the Ala

Wai in Waikiki, was going to Europe for some six months,

and she invited Mabel out to house sit while she was away.

So Mabel took a single stateroom on the Lurline, sailing

on June 9, 1939. This was Mabel's first trip to Hawaii since

her family had left there in 1903. It was to prove a spot

of great luck.

While helping a friend, Miss Haynes, who

operated the Ala Moana School, with her art classes, Mabel

suddenly realized just how much the Hawaiian race had been

diluted by foreign blood in the intervening years since she’d

lived there. It seemed to her that soon there would be no

Hawaiians left. The cliché "the

old Hawaii is gone forever" that had been repeated since

the first missionaries arrived in 1820 had at last fulfilled

itself. Mabel felt an urgency to paint and sketch as many

as possible of those Hawaiians that remained. So she had

her Los Angeles apartment closed and her little Plymouth

shipped out to her. She remained in Hawaii until mid-1940

and produced a wonderful collection of portraits, each labeled

with the complete blood mix of its subject. (It seems that

the plight of the Hawaiians was even worse than she thought,

for the only pure Hawaiian in this collection, as far as

we've been able to determine, was Abraham Kamahoahoa, the

deaf-mute boy.) It is probably the only such collection of

paintings ever produced. It was seen as a solo exhibition

in almost every major art museum along the West Coast during

the 1940s and at the Honolulu Academy of Art (her splendid

portrait of Mary Oneha is there in the permanent collection.

It was reproduced in David Forbes' 1992 book Encounters with

Paradise, Views of Hawaii and its People and in the April,

1999 issue of American Art Review magazine.).

During the war years Mabel did volunteer

work, primarily at the naval hospital in Long Beach helping,

through sketching and painting, the rehabilitation of the

injured servicemen. Nevertheless, the 1940s was a restless

decade for her. She felt her work had gone stale. She was

unable to find a new direction that interested and fulfilled

her, and she painted fewer finished pictures during those

years than during any other decade.

In 1953 Mabel took a trip through the

islands of the Caribbean. This opened up the new direction

she was looking for and put a new light into her palette

that would remain there until her last completed picture

in 1973. Reds and oranges and bright pinks and blues run

rampant through scenes of flower sellers, peasants' shacks,

tropical family groups. One of the most memorable of these

pictures, "The Blue House," a tumble-down

little shack with a rusty tin roof and bright blue walls,

had such an impact on the Haitian-born wife of the American

Ambassador to Nicaragua that she asked to borrow it while

they were there. In 1953 Mabel took a trip through the

islands of the Caribbean. This opened up the new direction

she was looking for and put a new light into her palette

that would remain there until her last completed picture

in 1973. Reds and oranges and bright pinks and blues run

rampant through scenes of flower sellers, peasants' shacks,

tropical family groups. One of the most memorable of these

pictures, "The Blue House," a tumble-down

little shack with a rusty tin roof and bright blue walls,

had such an impact on the Haitian-born wife of the American

Ambassador to Nicaragua that she asked to borrow it while

they were there.

The Mexican muralists, "los Tres

Hermanos," were

a major influence on Mabel's later work. She had long known

Ralph Stackpole, had in fact watched him at work on his famous

mural at the Coit Tower in San Francisco, and she was intrigued

by the work of Stackpole's close friend Diego Rivera and

that of David Alfaro Siqueiros. She also sought out Jose

Clemente Orozco during his time in Southern California and

watched him at work on his important mural at the Claremont

Colleges.

A trip through Mexico in 1955 added to

this new passion for color and increasing abstraction. That

trip inspired pictures of fruit markets, churches, public

festivals with streets full of celebrating people, fascinating

old buildings.

Mabel's last completed work, her 1973 "The

Man in Red" seems

to have brought her full circle in her lifelong spiritual

quest. An abstract oil and paper collage, it depicts a Rouault-like

Christ laboring under the weight of the cross, dressed in

the red of a Prince of the Church of her Spanish forbears.

On 13th March 1985, we were aware that

Mabel would almost surely not live through the night. Her

mind was clear as a bell, but the life was slowly, steadily

fading out of her body. She had spent the past couple of

years, after breaking a hip, in a large room in one of Los

Angeles' most comfortable nursing homes, surrounded by her

own elegant furniture and a small group of her favorite paintings.

Among her little connoisseur's collection

of books was a first-edition of Robert Louis Stevenson's A

Child's Garden of Verses. It seemed

just right that I should read to her from this book, after

Mrs. Rogers, her secretary/companion, had left and the

room was quiet. I read it from cover to cover while she

seemed to take quiet pleasure from Stevenson's special

words. But about mid-way through it I suddenly stopped

and said, "Mabel, I've

just thought of something. In future times Walter Alvarez

will be remembered only as Mabel Alvarez' brother. His

books have been out of print for years, but your work will

continue to delight people for centuries."

She opened her eyes and looked up at me. "You

know," she

said in a clear, strong voice, "I never thought of that!" She

passed quietly away a bit after 10 that night, in her ninety-fourth

year.

|