|

| |

| Following is an essay by Dr. Will South, noted

art historian and author, Director of the Weatherspoon Gallery,

University of North Carolina at Greensborough. This essay

was written for the 1999 “Mabel Alvarez, A Retrospective” presented

jointly by Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, and

the Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, California.

Reprinted by kind permission: |

| |

Mabel Alvarez Mabel Alvarez

In 1913, at the age of twenty-two, Mabel Alvarez (1891-1985)

received recognition for mural designs that were termed “half realistic

and half idealistic and wholly out of the ordinary.” 1 Here

was, as perceptive critic Alma May Cook noted (Los Angeles Express, September

13, 1913), a “promising young artist” from whom the community could

expect “something 'different' - tall and slim, she is of the pronounced

brunette type with dreaming eyes, just the type of artist to enter into all

myths and legends that are so dear to the mural painter.”

Mabel Alvarez exceeded expectations. For the next six

decades, she remained a provocative and productive painter - more adventurous

than the Impressionist-oriented instruction that formed her and less radical

than most emerging Modernist trends around her - but always sensitive, seductive,

and searching.

She was born on November 28, 1891, on the Island of Oahu,

Hawaii, the youngest of five children (fig.1). Her father,

Luis, was a Spanish-born physician; her mother, Clementine

Setza, came from a prominent St. Paul, Minnesota, family.

Luis and Clementine Alvarez relocated to Berkeley, California,

in 1906, and then in 1909 to Los Angeles, where their daughter

was a star pupil at the Los Angeles High School. Her art

teacher there, James Edwin McBurney, was responsible for

her early mural work: he had received a commission to create

murals for the Panama-California Exposition to be held

in San Diego in 1915, and engaged his former student to work

for him. Alma May Cook wrote that “demure, little

Miss Mabel Alvarez” had created a mural in which “every

stroke spells the poetry of springtime in California.” 2 Indeed,

Alvarez’s work at that time was marked by both

an interest in Symbolism and Art Nouveau and in the high-key

color and atmospheric effects derived from Impressionist

painting, a style then highly influential in Southern California

that she learned directly from her second important teacher,

William Cahill (1878-1924).

Cahill

had moved to Los Angeles in 1914 with fellow- Bostonian John

Hubbard Rich (1876-1954), and the pair founded the School

for Illustration and Painting. Here, Alvarez again found

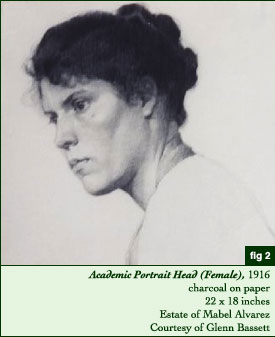

herself in the role of outstanding student: a drawing of

hers reproduced in the school’s 1916 brochure shows

extraordinary skill in academic rendering (fig.2). The ability

to draw well, to represent the illusion of three dimensions

accurately, was prized by American artists and was retained

even by those who, like Cahill and Rich, gradually adopted

the surface techniques of French Impressionism, such as bright,

outdoor color applied with loose, broken brushstrokes. 3 American

Impressionists rarely sought to dissolve form the way the

French had done, and Alvarez’s

youthful mix of careful rendering with an Impressionist-inspired

palette is typical of plein-air methods practiced in California

early in the century.

This mix is clearly seen in Alvarez’s

1919 Portrait

of Mrs. H. McGee Bernhart (fig.3), first shown at the

Tenth Annual Exhibition of the California Art Club. 4 The

sitter’s

features are definite and solid, while light and color flicker

around and on her in a manner derived from Cahill’s

well-known 1919 painting Thoughts of the Sea, featured in

the same California Club show. 5 Had

Alvarez focused on the development of a personal style of

California Impressionism, she might have become one of the

movement’s premier practitioners. Los

Angeles Times critic Antony Anderson wrote in his review

of this show that “This young artist, always an earnest

student, is advancing with much rapidity, doing better and

more distinguished work from year to year.” 6

However, her temperamental openness to new ideas and her

willingness to experiment kept her from fixating on one style or one teacher;

Alvarez was moving in different directions even as she embraced aspects of popular

regional painting.

While a student of Cahill’s, Alvarez was also taking

singing lessons, attending concerts and local exhibitions, meeting fellow artists

(including those with experimental tendencies like her own, such as Henrietta

Shore), and discovering the writings of Will Levington Comfort (1878-1932),

which would prove to be hugely influential on her thinking. Comfort was at the

center of a spiritualist colony in the Hollywood Hills, where he lectured and

monitored group meetings. There was a temple and a lotus pond on the grounds,

as well as a Greek theater. Alvarez attended many meetings at the colony, as

well as events in Comfort’s

home in Highland Park.

Comfort

advocated meditation as a way of beginning an inner journey leading ultimately

to a sense of harmony. 7 His ideas

were essentially Theosophical in content, blending aspects of different world

religions and taking the concept of karma as a central principle, that is,

that one’s future depends on events and attitudes in

his or her past. Linked to the belief in karma was the belief in “world

teachers” who come to earth in order to preach divine messages. Alvarez

found Comfort’s message “so much more practical than most church

sermons.”

Indeed, for Mabel Alvarez, even something as mystical and

mysterious as Theosophical thought had to have a “practical” appeal.

Her father was not only an esteemed doctor, but a shrewd businessman as well.

Her elder brother, Walter, became a well-known physician like his father, one

of many in the Alvarez clan to distinguish themselves in the sciences. Mabel

was not immune to the strong humanist inclinations of her family, and seems

to have balanced throughout her life a desire for the transcendental with an

unshakable conservatism that kept her rooted in the realities of time and place.

Her later retreat from Theosophy (though not from spirituality) may have been

linked to the scientific revelations of this century, well-known to Alvarez

through her father and brother, that directly contradicted the more esoteric

beliefs embraced by Theosophists. 8

From 1917 to 1920, many influences crowded into Alvarez’s

life in addition to the teachings of Cahill and Comfort. She kept meticulous

diaries from 1909 until her death, and recorded that in 1917 she read forty

books, including poetry by William Butler Yeats and short stories by August

Strindberg. Her first exhibition as a professional artist occurred at the San

Francisco Art Institute’s

annual show in 1918; 9 she joined the ranks of the powerful California

Art Club (an unabashed promotional vehicle for California Impressionist painting)

the same year, winning an honorable mention in her debut exhibit with that

organization; 10and

she received regular positive press for her painting (critic Pauline Payne

likened her color work to “mosaic”). 11 In

1919 she saw the canvases of modernist painter Birger Sandzén, whose

brilliant color so thrilled her that she wrote him a letter; she declined membership

in Henrietta Shore’s

Modern Art Society; she saw the paintings of one of California’s most

visionary painters, Rex Slinkard, which she called “dream worlds”;

and, in 1920, at the age of twenty-nine, she was part of a three-person (with

Loren R. Barton and Paul Lauritz) exhibition at the Los Angeles Museum of History,

Science and Art. Of this last achievement, an unidentified critic for the Los

Angeles Evening Express noted:

| Women are

honored with ‘one-man

exhibitions’ - and

you never heard of a ‘one-woman’ exhibition. However, the

work doesn't suffer and both Mabel Alvarez and Loren R. Barton are

winning new laurels in these exhibitions. Miss Alvarez, although a

young woman, has been known in the art exhibitions of Los Angeles for

several years. She has been doing some conscientious , as well as stunning

work, and her canvases hung on the end wall are all interesting.12 |

In

1919 Mabel Alvarez met the man who would have a profound influence on early

Modernist art in California, Stanton MacDonald-Wright (1890-1973). She became

his student, and her own words from 1928 describe the effect of his teaching:

| My

idea of painting is so different now from the formless idea of it I

had when I started. Then so much of our strength was just used up in

learning to handle this medium with all its difficulties. With Bill

[Cahill] we learned to paint in the Impressionistic manner with broken

color. We were never allowed to use black. As I remember he limited

us at that time to red, yellow and blue. I struggled for months with

the “direct” method

- a most difficult process. I suppose it was a good thing and gave

us a certain foundation and a certain amount of fluency. When I started

painting for myself alone, I gradually forgot all “methods” in

my interest in getting the feeling of things I wanted to do....Then

came the study in color and drawing with Macdonald-Wright. That opened

up a whole new world. I haven’t come to the end of it yet.13 |

Macdonald-Wright had left Los Angeles for Paris in 1909,

and it was there in 1913 that he and Morgan Russell (1886-1953) founded Synchromism.

The first avant-garde art movement started by Americans in Europe. He returned

to New York to exhibit at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery and in the Forum

Exhibition of 1916, but, tired of “chasing art up back alleys” in

the city, he went back to California in the fall of 1918. He began lecturing

and plotting the promotion of Modern art almost instantly - by 1920 he had engineered

the first exhibition ever of avant-garde painting in Southern California, an

event that paralleled (in a more modest way) the furor of New York’s Armory

show in 1913. Macdonald-Wright’s

fiery rhetoric, aggressive intellectual probing, and sheer artistic talent

inspired students such as Alvarez not to mimic him, but to find their own voice

by way of being introduced to a larger world of ideas and approaches than regional

Impressionism embraced.

In 1922 Macdonald-Wright took over the Los Angeles Art Students

League, where in 1924 Alvarez took notes and typed verbatim his rambling lectures

on aesthetics, which included ideas on ancient and oriental art. 14 One

of the first things students were told was that imitation by itself did not

make art: “Imitation thus

approximates but one world - that of objectivity, and if we consider the work

of art to be the entire expression of the man, it must be an equally balanced

manifestation of man’s existence in this dual world." 15 In

short, art needed the world of feeling, subjectivity.

It was in 1922 that Alvarez became a part of the “Group

of Eight,” painters

who banded together to promote their art which was veering further and further

away from the predictable standards of the California Art club. The Eight included

Alvarez, her former teacher John Hubbard Rich, Henri de Kruif, Luvena and Edouard

Vysekal, Donna Schuster, Roscoe Schrader, and Clarence Hinkle. Critic Antony

Anderson observed that the group had “some decidedly modern tendencies,” and

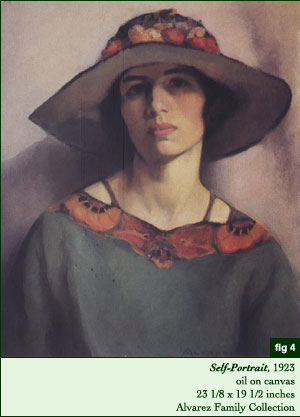

they did in relation to standard California Impressionist fare. Just how “Modern” Mabel

Alvarez was at this time is best revealed by one of the major paintings of

her career, her Self-Portrait of 1923 (fig.4).

Alvarez’s

image of herself is defined by broad areas of flat paint. The composition is

simple, symmetrical, and focused - a lean description of her face in basic

terms. The black line around the rim of her hat, which also appears on her

shoulder, is a device to frame color, picked up in Macdonald-Wright’s

class (one he himself adapted from Cézanne). The psychological presence

of the self-portrait declares itself in large measure by what it is not - clever,

formulaic, prettified, or imitative. It arrests the viewer’s imagination

by virtue of its relentlessly honest transcription. For Alvarez, and her audience,

this was Modernism in the tradition of Robert Henri’s economical, but

deftly painted, realism. This was not academic art or Impressionism as locally

practiced, with its careful drawing, pasted palette, and routinely picturesque

compositions - this was focused, abbreviated, enigmatic.

Alvarez’s self-portrait won the Women’s Federation

Prize that year, and was much reproduced in magazines and journals. In 1995

it graced the cover of Independent Spirits: Women Painters of the American

West, (1890-1945). 16

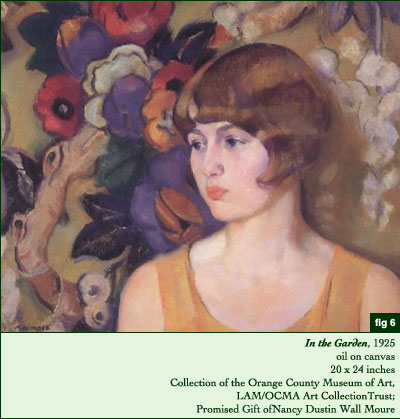

Alvarez went to New York in 1924 and when she saw some of

the more experimental painting, she wrote in her journal (without naming names), “Queer

modern stuff.” The pragmatic side to Alvarez resisted extremes - she never

attempted Cubist, Surrealist, or nonobjective painting. Nonetheless, true to

her experimental impulses, she created her own “queer modern stuff”the

very next year, a series of Symbolist canvases. She even joined the most radical

of art groups extant in Los Angeles at that time, the Modern Art Workers. Macdonald-Wright

wrote the group’s manifesto, which declared in part: “We feel the

time is ripe to get a more cosmopolitan atmosphere into the art life here,

build up some real vitalizing competition, and tear down a few “taboos.” 17

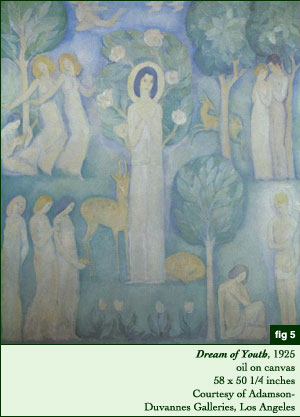

Alvarez’s large-scale 1925 painting Dream of Youth (fig.

5) is a fusion of the teachings of Will Levington Comfort, Theosophy, Macdonald-Wright,

with her own impulses toward the transcendent. It is an arcadian vision where

a Madonna-like woman blue hair and yellow halo occupies the center, where an

angel and two doves fly overhead, and where two lovers touch in the upper right

corner. It is at once an image of peace and of desire, of attainment and longing.

Just prior to painting Dream of Youth, she copied the following passage

from author D. H. Lawrence into her diary:

| That I am

I. That my soul is a dark forest. That my known self will never be

more than a little clearing in the forest. That gods, strange gods,

come forth from the forest into the clearing of my known self, and

then go back. That I must have the courage to let them come and go.

That I will never let mankind put anything over me, but that I will

try always to recognize and submit to the gods in me and the gods in

other men and women.”18 |

Color plays an important role in Alvarez’s symbolic

paintings. Green tinged with blue is the pervasive hue of Dream

of Youth, an

image of stillness and stability stemming from the central figure’s columnar

saintliness. In 1924 Macdonald-Wright had privately published his Treatise

on Color, distributing copies mainly to his students. Alvarez owned one. In his

Treatise, he discussed the emotional meaning of each color in the spectrum and

called green “a

disciple of non-action, of calm and of quiet.”

In addition to her knowledge of Macdonald-Wright’s

Treatise, Alvarez no doubt knew the work of German artist and spiritualist Wassily

Kandinsky, who called green “the most restful color that exists.” 19 And

of course her own studies in Theosophy that had begun years before taught about

color as symbol: noted Theosophists Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater published

Thought-Forms in 1902, which described blue-greens as showing “some of

the grandest qualities of human nature, the deepest sympathy and compassion,

with the power of perfect adaptability which only they can give.” 20

Green is the color of growth, of spring and of newness as

well as of calm and stability. Alvarez’s Dream of Youth may be

an expression of her own feeling of newness and growth. She may be the Madonna

in the center of the canvas, ready to accept change and to be a receptacle for

new life or perhaps a new way of living, as the Annunciation scene in the painting’s

lower right suggests.

In 1927 Alvarez was introduced to the work of Morgan Russell

when that artist had a joint show with Macdonald-Wright at the Los Angeles Museum.

She became more excited about the possibility of harmony in and through art. “The

more I think about it,” she wrote in 1928, “the more I think that

is the great thing to work for - beautiful color relationships... Thoughtless

painting won’t do anymore.”21 In 1931 Russell came to

Los Angeles for an extended visit, taught at Chouinard, and, as if by fate,

befriended her. Arriving on the cusp of Alvarez’s spiritual odyssey,

Russell may have seemed to her to be akin to a “world teacher” who

appeared to give her divine advice.

Morgan Russell talked to Mabel Alvarez about artists of common

interest, such as Henri Matisse, and he told her to become like a “cork

that floats downstream while painting,” to let the process take her where

it would. It was at this time, whether or not as a direct result of contact

with Russell, that Alvarez’s subject matter became less decorative, mystical,

and ambiguous, and more frankly sexual. She turned away from the symbolism of

the mid-to-late-1920s work to a series of realistic semi draped figures, most

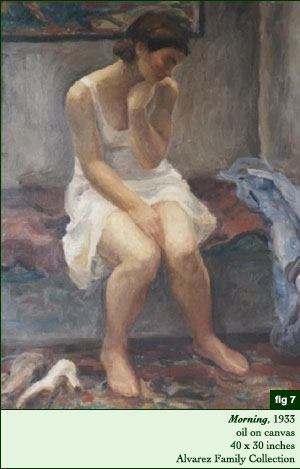

of them of her friend and favorite model Arabella. One entitled simply Morning (fig.

7) won the one-hundred-dollar first prize at the California Art Club’s

1933 Annual Exhibition. In this painting the female figure is seen from the

front, seated, with her head resting on her hand and her face turned away from

the viewer. She wears a white slip, her hand rests lightly between her thighs.

It is an image of restrained eroticism of quiet passion in subdued tonalities.

If every poem, painting and song is in some way autobiographical, this lightly

dressed figure evokes Alvarez herself, floating downstream as per the advice

of Morgan Russell and finding herself adrift in sensual reverie. Indeed, her

painting may have been the substitute for the relationship in life she always

craved but never found.

In 1931, the year she met Russell, Alvarez wrote a brief

article for the California Art Club Bulletin wherein she described

in no uncertain terms the importance of putting one’s self into the act

of painting:

| "Organization

alone does not make a work of art. There should be

a balance between the emotional content and the pure

form. Without a rich emotional and spiritual life,

with roots deep in nature, form alone is barren.”22 |

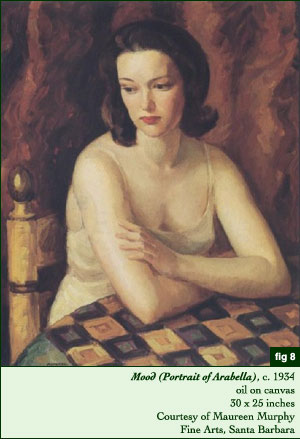

Another

striking image of Arabella is called Mood (fig. 8) , and features

the woman in the same white slip, seated at a table and looking away with

no particular focus. Again, the model’s hand rests softly on herself, this

time upon the arm. This painting was selected s one of only six to represent

the City of Los Angeles in New York’s Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Painting

and Sculpture from 16 American Cities.”23 Alvarez had arrived

on the national stage. Further confirmation of her recognition came in 1934

in Art

in America, In Modern Times, edited by Holger Cahill and Alfred H. Barr,

Jr. Mabel Alvarez was one of just three artists from Southern California mentioned,

the other two being Conrad Buff and Clarence Hinkle. Another

striking image of Arabella is called Mood (fig. 8) , and features

the woman in the same white slip, seated at a table and looking away with

no particular focus. Again, the model’s hand rests softly on herself, this

time upon the arm. This painting was selected s one of only six to represent

the City of Los Angeles in New York’s Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Painting

and Sculpture from 16 American Cities.”23 Alvarez had arrived

on the national stage. Further confirmation of her recognition came in 1934

in Art

in America, In Modern Times, edited by Holger Cahill and Alfred H. Barr,

Jr. Mabel Alvarez was one of just three artists from Southern California mentioned,

the other two being Conrad Buff and Clarence Hinkle.

In the 1930s Alvarez’s experimental searching nature

continued to manifest itself. Perhaps inspired by her friend Conrad Buff, one

of California’s

most accomplished printmakers, Alvarez made her first lithographs. Though

never prolific in this medium, she took lithography seriously and exhibited

her prints locally and in national shows. She also made ceramic tiles and

figures, working with her friend and fellow-artist Maxine Albro. And her most

experimental foray during the decade was her effort to become a writer. Alvarez

hired a professional writing teacher/consultant, and produced numerous short

stories. Despite her enthusiasm for the craft and a disciplined approach,

her stories are largely prosaic and remained unpublished.

The political images of he 1930s did not influence Alvarez

to create socially conscious art, though she very much admired the work of Mexican

muralists José Clemente

Orozco and Diego Rivera. Her attitude may have stemmed in part from the fact

that the Great Depression never affected Mabel Alvarez financially, as she

was supported by her father. When Luis Alvarez died in 1937, however, her

life did change in significant ways. Financially secure from her inheritance,

she left the large family home, moved to an apartment, and began to experience

bouts of depression.

Her sadness at this time may have been exacerbated by frustrations

related to her romantic relationship, begun in 1933, with Robert Kennicott.24 She

came very close to marrying Kennicott, and the end of their courtship must

have been difficult. When it ended, she wrote: “My life aimless now.

Needs more contacts.” In 1939, at the invitation of a friend, Alvarez

returned to the land of her birth, Hawaii. There, she made colorful portraits,

still lifes, and landscapes, and experienced a degree of spiritual rejuvenation.

In 1940 the artist was back in Los Angeles and was the subject

of a one-woman show at the Los Angeles Museum in August 1941 featuring the

work she had done in Hawaii. During the Second World War, she volunteered for

he Red Cross.

Into the 1950s Alvarez’s interest in discovering harmonious

color relationships continued unabated, though she now worked toward that

goal with subject matter derived from her travels, notably to the Caribbean and

Mexico: pictures of fruit markets, churches, and festivals became her staple

product. Stylistically her palette moved in a decorative direction, exploiting

the possibilities of bright pastels layered over each other with ethereal brushwork.

So enthusiastic was she for her new mode of working that she willingly painted

over some of her earlier canvases using her new approach. 25

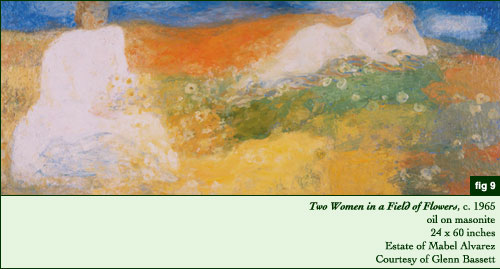

Typical

of her late work is Two Women in a Field of Flowers (fig. 9), which

alludes to stylistic influences from Milton Avery to Gustav Klimt. Here,

any vestige of the dark side of her earlier palette is gone as forms shimmer

and dissolve in fields of iridescent color. This painting also restates her

long-time interest in women as subject matter, and in themes of youth, growth,

and regeneration - all that flowers represent. However, these thematic impulses

that found expression in the Symbolist paintings of the 1920s and in the

fleshy, realistic painting of the 1930s are here an echo of that earlier

searching passion, a formal rearrangement of things remembered. Alvarez certainly

borrowed creatively from a variety of sources to keep her picture-making

fresh, but her inner journey, the one that had begun so long ago with Impressionist

seascapes and faces, had come to rest at a place where only the thoughtful

application of color - the “great

thing to work for” as she had written in 1928 - mattered. This enthusiasm

for color, deeply genuine and always carefully crafted, never waned. Typical

of her late work is Two Women in a Field of Flowers (fig. 9), which

alludes to stylistic influences from Milton Avery to Gustav Klimt. Here,

any vestige of the dark side of her earlier palette is gone as forms shimmer

and dissolve in fields of iridescent color. This painting also restates her

long-time interest in women as subject matter, and in themes of youth, growth,

and regeneration - all that flowers represent. However, these thematic impulses

that found expression in the Symbolist paintings of the 1920s and in the

fleshy, realistic painting of the 1930s are here an echo of that earlier

searching passion, a formal rearrangement of things remembered. Alvarez certainly

borrowed creatively from a variety of sources to keep her picture-making

fresh, but her inner journey, the one that had begun so long ago with Impressionist

seascapes and faces, had come to rest at a place where only the thoughtful

application of color - the “great

thing to work for” as she had written in 1928 - mattered. This enthusiasm

for color, deeply genuine and always carefully crafted, never waned.

Alvarez continued to paint through her sixties and seventies,

and to exhibit regularly, including with the Women Painters West organization.

The later years of her life were spent in a retirement apartment and then

in a nursing home. She died on March 13, 1985, at the age of ninety-three.

Mabel

Alvarez will be remembered for her contributions to California Impressionism

a well as to figure, still-life (fig. 10) , and portrait painting. Collectors

and scholars will continue to study the significant role she played during

the fitful and sporadic emergence of Southern California Modernism, when

there were so few willing to extend the boundaries of locally accepted painting.

Finally, the art of Mabel Alvarez will be admired and enjoyed by generations

to come for its sensitive and thoroughly professional legacy on canvas, one

of sensual variety, quiet contemplation, exuberance, and joy. Mabel

Alvarez will be remembered for her contributions to California Impressionism

a well as to figure, still-life (fig. 10) , and portrait painting. Collectors

and scholars will continue to study the significant role she played during

the fitful and sporadic emergence of Southern California Modernism, when

there were so few willing to extend the boundaries of locally accepted painting.

Finally, the art of Mabel Alvarez will be admired and enjoyed by generations

to come for its sensitive and thoroughly professional legacy on canvas, one

of sensual variety, quiet contemplation, exuberance, and joy.

- Will South

The author dedicates this brief essay to Pauline Khuri-Majoli,

former professor or art at Loyola Marymount University, who brought both her

own formidable talent as well as the work of Mabel Alvarez to class for her

students to experience.

Notes

1 Alma May Cook, “Promising Young Artist Has Exhibit Particularly Beautiful,” Los

Angeles Express, September 13, 1913, in Mabel Alvarez Scrapbook, Archives

of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (cited hereafter as Alvarez Papers

AAA).

2 Alma May Cook, “War Brings New Era in Art - America for American,” Los

Angeles Tribune, August 30, 1914, Theater, Music and Art section, (photo of

Alvarez and her mural), p. 3.

3 For an in-depth overview, see Will South, California

Impressionism, with

an introduction by William H. Gerdts (New York: Abbeville Press, 1998).

4 Formally untitled, this painting is clearly described, though not titled,

in a review of that exhibition. See Alma May Cook, newspaper clipping from

the Los Angeles Express, October 11, 1919, in the Los Angeles Museum

of History, Science and Art Scrapbooks, on file at the Los Angeles County

Museum of Natural History. The title is then given to Antony Anderson’s review of the same

show: see his “Of Art and Artists,” Los Angeles

Times, October

12, 1919.

5 William V. Cahill, Thoughts of the Sea, 1919, oil on canvas, 40X391/2 inches,

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Gerald D. Gallop, is reproduced in South, p. 64.

Alvarez saved a photograph of Cahill painting Thoughts

of the Sea in her scrapbook,

Alvarez Papers AAA.

6 Anderson, “Of Art and Artists”.

7 Of his beliefs, Comfort wrote: “My love for the Bible today

and for the Sacred Writings of the Father East, as well as the uncommon

inner tendency of my work as a modern American novelist are all directly

traceable to that first little book of Mrs. Besant’s, Thought Power,

my greatest reading experience.” Quoted in The International

Theosophical Year Book 1937 (Adyar, Madras, India: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1937),

p. 196. The author thanks Lakshmi Narayan, head librarian of the Krotona Library,

Ojai, California, for assistance in finding information on Comfort.

8 In Annie Besant’s Thought Power, a standard work among Theosophists

first published in 1903, and most certainly known to Mabel Alvarez, Besant

describes the curing of alcoholism by sitting next to the sleeping patient

and concentrating on images that would “vibrate” into the victim,

thus effecting cure. Such unscientific methods would have been anathema to

Luis and Walter Alvarez, and, as Mabel Alvarez had great confidence in both

her father and her brother, one can imagine their influence chipping away

at her own faith in this particular system.

9 The San Francisco Art Association’s Annual Exhibition by Contemporary

American Artists, March 22 - May 22, 1918, at the Palace of Fine Arts, Alvarez

exhibited The Breakfast Room and The Brass Bowl .

10 California Art Club’s Spring Exhibition, April 4-30, 1918, at the

Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art, Exposition Park. Alvarez

showed two works, Portrait of Miss C. and Blue and Gold.

Honorable Mention was for Miss C., and carried a twenty-five dollar prize.

Alvarez also showed in the club’s fall exhibition, and received the

following notice in the Los

Angeles Times: Mabel Alvarez shows ‘Above the Sea’ and has caught

the vastness of the ocean and the brilliant sunshine” (November 22, 1918).

Alvarez became a very active member of the California Art Club, serving on

various committees (including chairperson of the Art Committee), serving as

a juror, and acting as a sometime editor and contributing writer to the Club’s Bulletin.

11 Pauline Payne, “Paintings pf Wide Variety Displayed to Advantage

at Liberty Exposition,“ Los Angeles Evening Herald, December, 1918, clipping

in Alvarez Papers AAA.

12 “L.A. Girl Artists Win New Laurels by Display at Exposition Park

Gallery,” Los

Angeles Evening Express, November 26, 1920.

13 Alvarez Papers AAA

14 Stanton Macdonald-Wright, “Lectures to the Art Students’ League

of Los Angeles” (hereafter ASL Lectures) recorded and transcribed by

Mabel Alvarez, Museum of Modern Art Library, New York. Xerox copy from the

original in possession of the author, courtesy of Pauline Khuri-Majoli, Los

Angeles.

15 Ibid., p. 1.

16 Patricia Trenton, ed., Independent Spirits,

Women Painters of the West, 1890-1945 (Los Angeles: Autry Museum of

Western Heritage in association of the University Of California Press, 1995).

In this catalogue Alvarez is authoritatively discussed in context by Ilene

Fort in her essay “The

Adventuresome, the Eccentrics, and the Dreamers: Women Modernists of Southern

California.”

17 Macdonald-Wright, “An Open Letter From a Modernist,” Los

Angeles Times, October 4, 1925, p. 35. In this letter, Macdonald-Wright noted that

George Stojana was president, Mabel Alvarez was vice-president, and Eduoard

Vysekal was treasurer.

18 Alvarez Papers AAA. Lawrence’s quotation is from Studios

in Classic American Literature.

19 Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art (New York: Dover Publications,

1977, reprint of original 1914 edition) p. 38.

20 Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, Thought Forms (Adyar, Madras, India:

The Theosophical Publishing House, 1925, first published 1902), p. 69.

21 Alvarez Papers AAA.

22 Mabel Alvarez, “More About Organization,” California

Art Club Bulletin 6, 3 (March 1931), p. 6.

23 New York, The Museum of Modern Art, “Painting and Sculpture from 16

American Cities,” 1933. The other artists representing Los Angeles

were Conrad Buff, Clarence Hinkle, John Hubbard Rich, Edouard Vysekal, and

William Wendt.

24 It has been suggested by more than one person interviewed for this essay

that Mabel Alvarez’s relationship with Kennicott dissolved when she

discovered he was homosexual. Reared to be socially prim and proper, she may

have been naïve enough not to intuit Kennicott’s orientation. In

her diaries Alvarez does not discuss her own sexuality. An in-depth study of

Alvarez’s life, sure to come given her growing stature in Californian

art, may clarify certain aspects of her private life that remain, for now,

speculative. The author thanks Glenn Bassett for his invaluable assistance

in providing insights into and information on the artist’s life for

the present study.

25 She was admonished for this practice in a 1960 letter to her from Earl

Rowland of the Pioneer Museum & Haggin Galleries in Stockton, California. “Now

I have a few things to say that might be interesting to you. You greatly shocked

me when you said you are painting over some of your old canvases and doing

things in your new style on top of them. This worries me. Such a practice could

only arise from two causes. One, that you fail to appreciate your older work

sufficiently and two, that the purchase of materials is a problem with you

which I think is not likely to be the case.” Alvarez Papers AAA.

|

|

|

|

|